By Jessica DeWitt

Watch the accompanying video here.

Every month we carefully track the most popular and significant environmental history articles, videos, audio, and other items making their way through the online environmental history (#envhist) community. This month we have an accompanying video. Let us know what you think of the new video feature in the comments. Here are our choices for items most worth reading from September 2014.

1. Here’s Every Single Animal That Went Extinct In the Last 100 Years

Animal topics were quite prevalent in September. One of the most popular articles this month was a list of every animal that has become extinct in the past one hundred years. The list is simple, only providing a photograph or painting of the extinct animal, but still packs an emotional punch. There is something eerie about looking at a species that no longer exists and will never exist again. The list elicits many unanswered questions about how and why these species went extinct and thus is good fodder for future environmental history inquiries.

2. Where are the animals in the history of sexuality?

Another popular animal history post this past month comes from the history of sexuality blog, Notches, and was written by Gabriel Rosenberg, a professor at Duke University. In the blog post Rosenberg questions why animals are typically left out of the history of sexuality and challenges historians of sexuality to move beyond bestiality when considering animal/human sexual relations. Looking at the “Van Briggle Breeding Crate,” Rosenberg looks at the ways in which humans have manufactured animal sex for their own benefit, thus making them necessary components in animal sex and desire. This is one of those topics that beautifully pulls together various fields of history: environmental and agricultural history are melded with the history of science and sexuality. On Twitter Dan Rueck stated, “This is the best thing I’ve ever read on the history of pig sex,” and I would have to concur.

3. Untrammeled: Americans and the Wilderness

There were a lot of pieces written this month in relation to the 50th Anniversary of the Wilderness Act in the U.S. One of the best commemoration efforts was produced by BackStory Radio. They recorded a podcast called “Untrammeled” which explores various aspects of the wilderness concept in American history. They discuss colonial New England and the non-pristine nature of the forests in the region with Charles Mann, the creation of wilderness conditions during the Civil War with Lisa Brady, the battle over Hetch Hetchy between Gifford Pinchot and John Muir, the eviction of people from the land that would become Shenandoah National Park, and Emma Marris and Paul Sutter discuss whether any land can still (or ever) accurately be called wilderness.

4. War Against Nature, the Backbone of the South

Lisa Brady makes another appearance in Jacob Darwin Hamblin’s latest environmental history roundtable pertaining to Brady’s book, War Upon the Land. Referring to Donald Worster’s call for agroecological perspectives, Hamblin asks, “…how conscious of these connections were the people living in the mid-nineteenth century? How did they imagine their own control over the landscape, and their own vulnerability?” Brady, Matthew Denis, Ann Norton Greene, and Megan Kate Nelson discuss these questions and Brady’s book in a roundtable that is free to access on H-Net Environment.

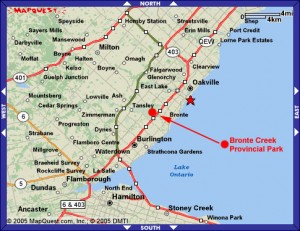

5. Suburbia and the Creation of Anti-Indigenous Space

Nathan Ince, a graduate student at York University, launched a new research blog this month. One of his first posts is a thought-provoking piece on the relation of suburban development, specifically in Waterdown, Ontario, to environmental history and the erasure of Indigeneity. Ince writes that “this process of suburbanization could almost be viewed as a ritual of purification, as a potentially contested landscape is transformed into a sort of anti-Indigenous space, where not even memory of First Nations occupation is able to survive. While the process might not be conscious, it serves an undeniable purpose in Canadian society. Through a comprehensive transformation of the landscape, we are absolved of the sins of the past.”

Remember to follow #envhist hashtag and NiCHE (@NiCHE_Canada) on Twitter, Facebook, and Google+ to keep up with the latest environmental history content.